TheoAnthropos: The Mystery of Christ’s Two Natures and the Theology of Redemption Introduction

TheoAnthropos: The Mystery of Christ’s Two Natures and the Theology of Redemption

Introduction

Christian theology is not merely a systematic doctrine but an existential response to the deepest questions of the human being. At the very center stands the Person through whom God fully reveals Himself – Jesus Christ. The question “Who is Christ?” is neither solely historical nor dogmatic; it touches the essence of the human person, their redemption, and identity. Understanding the two natures of Christ – divinity and humanity – is the core of soteriology, the doctrine of salvation. If Christ is not fully God, He cannot save. If He is not fully man, He cannot represent us. This study proceeds from the concept TheoAnthropos – God-Man – and explores how this mystery opens to us the nature, scope, and psychological meaning of redemption.

TheoAnthropos – The God-Man

The term Θεάνθρωπος (TheoAnthropos) denotes Christ as the Person who unites in Himself complete divinity and complete humanity. This is not a mixture or alternation of two natures but their full co-existence in one Person. The Council of Chalcedon (451) formulated this mystery as a union of two natures “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” This definition is not merely dogmatic but profoundly existential: it declares that Christ is neither a demigod nor a merely inspired human, but true God and true man.

The divinity of Christ means that He is eternal, omnipotent, and omnipresent. His divine nature ensures that redemption is not simply an ethical example or a moral teaching but God’s own saving act. At the same time, His humanity means that He has shared our existence – pain, suffering, and death. This makes Him not only Redeemer but also our representative and High Priest who understands our weaknesses.

TheoAnthropos is not merely a theological concept but a horizon of meaning that calls the human person into communion. Christ as God-Man is the bridge between the infinite and the finite, eternity and time, Creator and creation. In His Person, all contradictions that often appear in human experience – the sacred and profane, eternal and transient, omnipotent and vulnerable – come together.

Such an understanding of Christ also establishes a new foundation for human identity. If God has taken on human nature, then humanity itself has received a new dignity. Through Christ, human existence has acquired a divine dimension – not only the possibility of redemption but also of deification.

TheoAnthropos: The Mystery of Christ’s Two Natures and the Theology of Redemption Introduction

The Divinity of Christ

The divinity of Christ means that He is eternal, omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient. In the Gospel of John it is said: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

Christ’s divinity ensures that salvation is the work of God Himself, not merely a human effort. Only God can forgive sins and restore the broken relationship with the Creator. Christ’s resurrection confirms His divine power over death.

The Humanity of Christ

Christ was born of a woman, lived a human life, experienced pain, hunger, sorrow, and died. His humanity was not an illusion but a full participation in the human condition. As St. Gregory of Nazianzus said: “What is not assumed is not healed.”

Christ’s humanity means that He can be our High Priest who knows our weaknesses (Heb. 4:15).

The Scope of Redemption: Soteriology as a Cosmic Narrative

Soteriology, from the Greek σωτηρία (salvation), is not merely one doctrine among others. It is the grand theme of Scripture, encompassing all of human history and eternity. According to an article on Bible.org, soteriology is “the greatest theme of the Bible,” affecting every person and even the angelic world. It is God’s plan of salvation with Christ – the TheoAnthropos – at its center.

Soteriology is not limited to forgiveness of sins. It includes redemption, atonement, justification, regeneration, sanctification, and finally glorification. It is God’s complete work on behalf of the human person – delivering them from the bondage of sin, death, and spiritual death. This work is not the result of human merit but the fruit of divine grace. Christ’s death and resurrection are the core of this work – “It is finished” (John 19:30) signifies not only the end of suffering but the full completion of salvation.

Soteriology is also three-dimensional: in the past (saved from the penalty of sin), in the present (saved from the power of sin), and in the future (saved from the presence of sin). This dynamic demonstrates that salvation is a process that begins with faith, continues in sanctification, and culminates in glorification. It gives the believer confidence and calls them to grow in Christlikeness.

The work of Christ is not only individual but also cosmic. His redemptive work extends to the restoration of all creation – “the whole creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (Rom. 8:19). Thus soteriology is linked to eschatology – the future hope in which the Kingdom of God is fully revealed.

Ultimately, soteriology is the revelation of God’s love, holiness, and justice. It shows that God does not tolerate sin, yet loves the sinful human being so much that He gives His Son. This paradox – justice and mercy – finds its resolution only in the Cross of Christ.

Atonement and Reconciliation: Removing the Barrier

Between God and humanity stands a barrier – sinfulness, spiritual death, God’s holiness, and human unrighteousness. This barrier is not merely moral but ontological – it touches the very nature of the human person. In this context, the doctrine of atonement is central: how can a holy God accept a sinful human being?

Atonement means that Christ, by His death, has satisfied the demands of divine justice. His sacrifice was not merely symbolic but real and sufficient. Christ’s death removes the barrier that separated humanity from God. This is not a mutual compromise but a unilateral act of grace – God reconciled the world to Himself through Christ (2 Cor. 5:18–19).

Atonement also includes justification – God declares the sinner righteous not because of their works but through faith in Christ. This is a judicial act in which the condemned is declared righteous because Christ has borne the punishment. It also includes regeneration – the work of the Holy Spirit who gives a person new life and spiritual capacity.

Atonement is not only vertical (God–human) but also horizontal – it restores relationships between people. Christ is “our peace,” who has broken down the dividing wall (Eph. 2:14). Thus soteriology is also a social doctrine – calling for reconciliation, forgiveness, and communion.

Finally, the work of atonement is a finished work. Christ’s words on the Cross – “It is finished” – mean that nothing needs to be added. Human beings cannot earn salvation but only receive it. This is the mystery of grace, calling us to humility and gratitude.

Christ and Psychology: Overcoming Inner Fragmentation

The understanding of Christ’s two natures is not only theological but also psychological. Humans are inwardly fragmented – their ideals and reality, desires and fears, guilt and need for redemption. Christ as TheoAnthropos embodies this fragmentation and offers a way to overcome it.

In psychoanalytic terms, Christ’s divinity may be understood as the Superego – the ideal self that represents eternal order and moral absolutes. His humanity embodies the Ego – the vulnerable, experiencing self that faces suffering, fear, and death. On the Cross, these two meet – this is a psychic integration in which the human being receives redemption through acknowledging their brokenness. Christ’s sufferings are not only a historical event but a psychological process.

Hermeneutical Deep Study

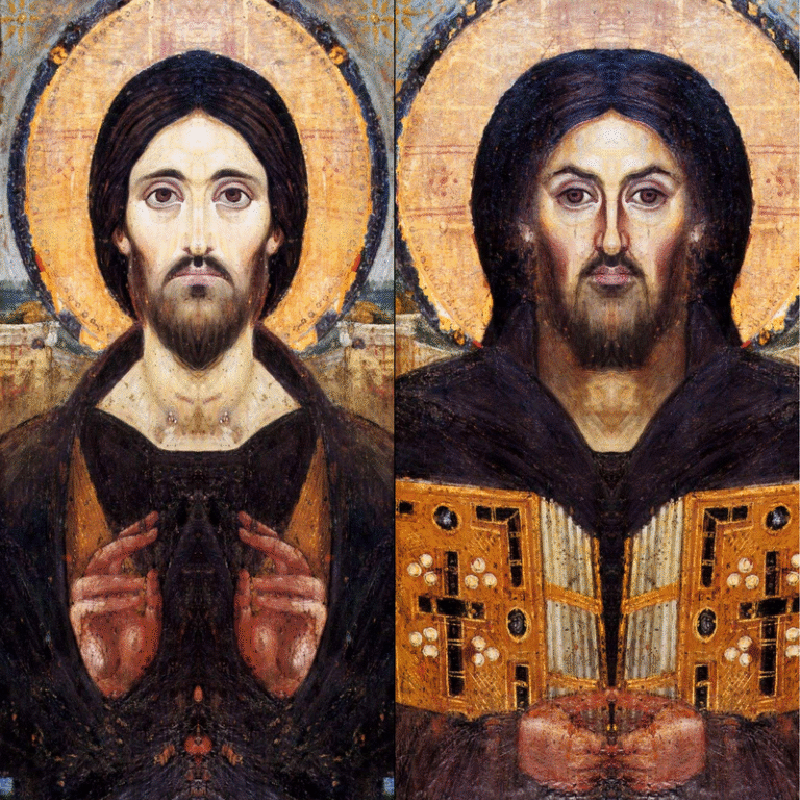

Hermeneutically, Christ is a “text” that unites history, tradition, and existence. Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Trinity, interpreted through Martin Vaik’s concept of the “Singular Trinity,” shows how the presence of Christ can manifest even within fragmented, postmodern aesthetics. Christ is not a static dogma but a living circle of meaning that invites the viewer into communion – even through chaos and discontinuity.

Soteriology: The Doctrine of Salvation

Soteriology (Gr. σωτηρία – salvation, λύω – to set free) concerns God’s plan of deliverance for humanity. According to Bible.org:

“Soteriology, the doctrine of salvation, is the greatest theme of the Bible. It encompasses all time and eternity and concerns all of humanity.”

Soteriology includes the following key elements:

• Atonement – Christ’s death as the sacrifice that satisfies God’s justice.

• Redemption – liberation of the human being from the bondage of sin and death.

• Justification – God’s declaration of a person as righteous through faith.

• Regeneration – the work of the Holy Spirit giving new life.

• Sanctification – the process by which a person becomes more like Christ.

A Critique of Calvinism

Calvinism emphasizes God’s sovereignty and teaches that salvation is predestined only for the elect. However, this viewpoint can lead to determinism and a restriction of grace. From an Orthodox perspective, this is problematic because:

• Human free will is essential for cooperation with divine grace.

• Apokatastasis, the restoration of all things, is the Orthodox hope – not salvation for the elect alone.

• The Calvinist doctrine of limited atonement (that Christ died only for the elect) contradicts 1 John 2:2:

“He is the atonement for our sins, and not for ours only, but for the sins of the whole world.”

Psychological Analysis: Christ as Inner Archetype

Christ as TheoAnthropos embodies the inner fragmentation of the human being and the possibility of its integration. In psychoanalytic terms:

• Christ’s divinity represents the Superego – the ideal, eternal order.

• Christ’s humanity embodies the Ego – the vulnerable, experiencing self.

• On the Cross, these two meet – a psychic integration in which the person finds redemption through acknowledging their brokenness.

Analysis

Understanding Christ’s two natures is not merely a dogmatic question but a question of salvation and identity. TheoAnthropos unites heaven and earth, eternity and time, God and humanity. Soteriology is not only forgiveness of sins but communion in the life of Christ – the path to deification. The Calvinist concept of limited grace is narrow when compared to the Orthodox vision of all-encompassing redemption. Christ is not only a historical figure but an existential horizon calling every person into communion – not through perfection but through vulnerability.

Author Introduction

Martin Vaik (artist name Singular) is a theologian, hermeneutic thinker, and aesthetic philosopher whose work unites visual art, theology, and psychoanalysis. He leads the think tank AICortexSingular and studies how contemporary culture reflects spiritual questions.

Europe Heaven Invest 2072 Gold OÜ – 2025